Making the case for program investment and seeing the resulting growth in giving may be among my favorite roles as a fundraising consultant these past 17 years. I can speak confidently because the data is sound. I can speak with credibility because I am not asking for my own resources, rather making the case for somebody else. And I can speak with empathy for all of the roles in development, having had personal experience in advancement operations.

Why is it so hard to secure investment for non-frontline roles? Perhaps the easiest answer is to acknowledge that leadership rarely has a fundraising background. But leaders are more likely to interact with the frontline officers. Their experience with fundraising is seeing and perhaps participating only in the cultivation and asking process. Their line of sight to the rest of the organization is limited. And it makes common sense for them to think fundraisers are the ones raising funds.

As I think through my successes in building advancement operations investment, I’ve followed a rather consistent methodological path. I’m hoping these techniques equip you to make similar cases at your organizations. Of course, we are always here to walk with you to be a source of analysis or a vicarious voice in the discussion.

1. Returns vs. Cost

When you talk about your program—whether or not you are asking for resources—use return on investment language. The phrase “cost to raise a dollar” should never originate with you. If asked about the cost to raise a dollar, be like a politician and pivot the dialogue to return on investment.

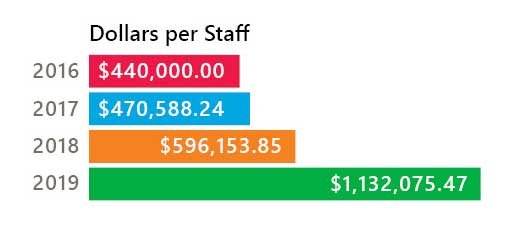

In your reporting, have regular analysis on the return on investment of all staff and the contribution to your operating margin as an institution. I find it effective to add correlation coefficients to show that revenue per staff actually increases with overall staff volume. In the reverse, this establishes the precedent that any cuts in a program would also dig deeper than the cost savings of the salary costs.

Use investment language when discussing return on investment. Rather than say we have a $0.25 cost to raise a dollar, say we are maintaining a 400% return on our staffing investment. A fun way to do this is to compare your returns to top performing stocks. Say things like our team had a higher return than Tesla stock this quarter.

Although this first step does not directly address advancement operations yet, it is beginning to the shift the narrative in your favor in a few advantageous ways:

- You are strengthening the overall program reputation as a revenue center.

- The likelihood to be considered equally in across-the-board cuts decreases.

- You are providing leadership confidence that the program value to the operating margin is supported by evidence, rather than being another department using only self-interest or opinion to ask for resources.

2. Operations Ratio to Production

In our analysis of institutions across sectors, we consistently see a correlation between the operations-to-frontline ratio with revenue goal attainment. In other words, as the number of advancement operations staff increases when compared to fundraiser counts, the incidence of organizations hitting their goals increases.

At the individual organization level, we have also run this comparison. In the following example (numbers changed to provide anonymity), this organization met their own goals in years when they were better staffed in advancement operations.

- We hit our goal when we had more operations staff.

- Decreases in staff reduced revenue by 2.7x staff costs.

Perhaps the numbers do not calculate the same for you. At this point, our analysis has revealed the correlation. We can’t yet prove the causation—but we are getting close. The key drivers dictating the correlation appear to be related to cost allocation related to duties, which leads us to our next step:

3. Top of License

Healthcare organizations are accustomed to the phrase “top of license.” Law firms and big consulting firms often use a similar phrase, “lowest cost biller.” The principal is the same. In the healthcare usage, doctors or specialists might be the highest paid and most competitive resource. If there are tasks that others could do at the hospital to free the physician for higher value tasks, they will staff accordingly. Similarly, a partner at a law firm will not draft your will. They will have a paralegal do this at a lower price point. A general evaluation for top of license or lower cost biller is:

- Can someone provide the same value for less cost?

- Can someone provide more value for the same cost?

- Can the work be scaled with technology or process to reduce cost?

In fundraising, sometimes we will conduct a time audit of the frontline officers. In simple terms, this is capturing the percentage of time spent doing various tasks including things like interacting with donors, writing proposals, coordinating with organizational partners, reviewing research, determining strategy, checking on the use of funds, stewardship, and so on. Then we look at these items against the top of license evaluation criteria. If two fundraisers at $100,000 price points were spending 50% of their time fundraising and 50% of their time doing something else, but a advancement operations person at $80,000 could do the other stuff, the staff cost of the same work could be $180,000 instead of $200,000. Extrapolating out this principal can actually increase frontline activity and philanthropic revenue by only adding operations staff.

4. Yield Analysis

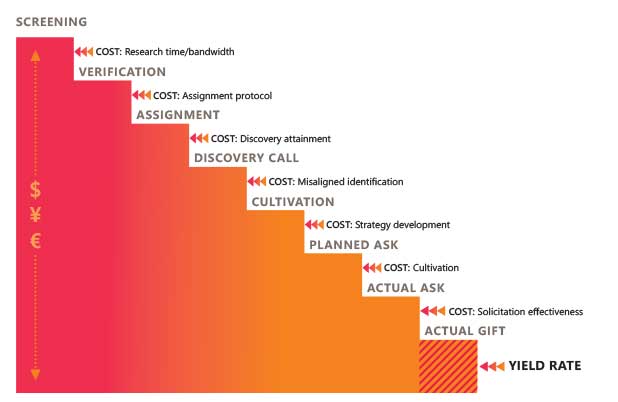

An increasingly popular measurement of fundraising programs is the yield rate. The statistic can mean different things for different organizations. For some, it can be specific to the close rate. In other words, “What are we yielding on solicitations? 50% of asked? 75% of asked?” For others, it might mean the philanthropic share of wallet of the entire constituency capacity or specific pool. In other words, “We are yielding 1.5% of the philanthropic capacity of our database.” Or, “We are yielding 6.5% of the capacity of our major gift prospects.”

If we consider yield to be inclusive of these various perspectives, it can be very helpful to staff resource investment analysis for both the frontline and advancement operations. For example, if an organization is raising 1.5% of the overall file capacity, what were the cost reductions? Or where did the other 98.5% go? This poses the question of prospect development and pipeline efficiency.

- If everyone is screened, but only some portions are research verified, there is a cost against the yield of our research verification processes or staffing.

- If only some of the names attempted to be verified are indeed appropriate prospects, there is cost against the yield of our screening and analytics effectiveness.

- If only some of the names verified are assigned, there is some reduction related to organizational assignment protocols.

- If officers only conduct some discovery calls on some portion of the assigned names, there is a cost related to discovery call attainment.

- If after the discovery call, a lead is deemed not a prospect, there is a cost of misaligned identification.

- If the new name has a cultivation strategy with a planned ask less than the capacity rating, there is a further yield reduction.

- If the ask is lower than planned, it is reduced once again.

- If the funded amount is less than the asked amount, the yield is further reduced.

All of these steps factor into the overall yield rate. But not all of these steps are managed by the frontline team. For example, increasing the verification volume from the prospect development team will have a ripple effect on the total yield rate. This work is done by advancement operations.

5. Classify ROI-Related Outcomes

Although total dollars raised, operating margin contribution, or total net revenue is the most common measure in evaluating staffing or resource investment, it is limiting in classifying the value in a more comprehensive way. Most CFOs, for example, will weigh risk just as high as reward at many organizations. I like to align all activities to various outcomes in making the case for their value.

- Revenue returns. In addition to the ways described previously, I find it valuable to show the short-term returns (gifts now), long-term returns (pipeline development), and emergency response and recovery (endowment, disaster response, pandemic needs, etc.).

- Risk management. Risks could include due diligence necessary in vetting donors in cases of inappropriate action or influence, legal exposure, funds management and security, technology breaches, and even activities that distract the frontline from bringing in revenue.

- Continuity. Many programs will sacrifice the long-term benefit for the short-term gains. But they will rarely see that the short-term benefits were only possible because of previous long-term investments. In times of disruption, certain staff roles, technologies, and processes are essential to remain functional as an organization. If they went away, there could be continuity risk or increased cost of recovery.

- Versatility and adaptability. The events of 2020 shifted to a greater share of philanthropic giving coming from the high-net-worth constituents. Staff members with versatility to do other things like prospect development or servicing major giving officers were often temporarily repurposed to focus on those areas. Also, many events programs shifted the balance to more high-touch virtual events. Phone programs needed to adapt to the rapid growth in multichannel and digital programs. Clearly articulating versatility helps in making the case for hiring and keeping people.

- Outsourcing opportunities. Although outsourcing might seem counterproductive to staff investment discussions, we’ve seen the opposite. The willingness to entertain outsourcing options can bring confidence that you are evaluating what makes the most sense for the institution and not just for you. Outsourcing certain work can make the other work more interesting or valuable to your existing staff. And it might be an important gap filler to preserve resource investment during staffing freezes.

These are only a few examples of how we approach the question of advancement operations ROI. Most of my learning is from working with you and the great nonprofits, hospitals, and universities you serve. I would love for that learning to continue. Drop me a note. Reach out to our decision science team who digs into this data every day. Drop a line to your BWF contact. Our goal is to empower you and share your success. We will always be there to help you make the case for your advancement operations team.